In our last post we outlined the evidence that there is a disconnect between the preparation universities provide and employer expectations – a ‘skills gap’. We believe universities can get much better at helping students make the transition to the work world and launch a great career, but to succeed they will need much stronger partnerships with willing students and employers.

We also believe universities that prepare more employable graduates will be living their mission of providing a broad, general education and preparing students to be engaged citizens, not compromising that mission nor turning into career and technical education programs (which are important for different reasons). One thing is sure: universities that close the skills gap will earn favor with students, parents, employers, and elected officials.

Getting to Why

Solving any problem means getting to its root cause. So, why does the skills gap exist? That is a simple question without a simple answer. First, there are multiple actors involved - students, universities (faculty, staff, and administration), and employers. Each of these groups is comprised of individuals and organizations with their own sets of motivations and constraints, some of them conflicting. What is best for employers is not always best for students, and both students and employers struggle to understand the mission of universities extends beyond career preparation. On top of these factors, universities are large and complex places, which leads to incredibly complicated (and confusing!) interactions between students, the university, and employers.

Sorting out where in this complex system the breakdowns occur and where improvements can be made is not straightforward. Much of the criticism tends to focus on individual actors – students and universities especially. We will outline some of these criticisms to provide context on where key issues reside. That said, in this post and the next four posts to follow we will argue that a more important – and less obvious - set of factors are at play which impede alignment between student goals, university preparation, and employer demands.

Are Students To Blame?

Some argue the skills gap is the result of the current generation of students and their attitudes toward work (and life). Employers say Gen Z brings an attitude of entitlement, they aren’t engaged or interested, they get offended easily, they don’t respond well to feedback, they lack work ethic, they lack motivation, they are hard to manage. That sounds bad!

But where do these attitudes and behaviors come from? Some don’t blame the students themselves for their faults, they place the blame more broadly on ‘culture’, parents, and the pandemic. And, even personal attributes can be affected, for better or worse, by the quality of the education students receive.

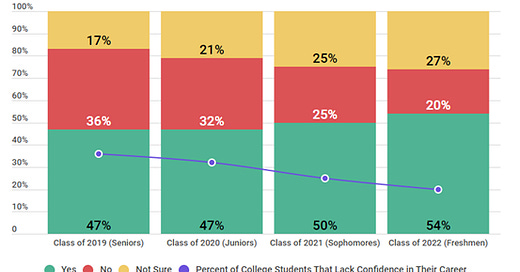

Source: Intelligent

Even if we focus only on students’ preparation for employment, we can find systemic problems that go far beyond student attitudes. One study found that 50 percent of college graduates (two- and four-year) didn’t apply to entry-level jobs because they felt underqualified, with 21 percent indicating their college didn’t provide them with needed job-ready skills. While experiences such as internships are highly valued by employers, many students cannot access such experiences for financial or family reasons. In other cases, students may struggle to communicate the skills they actually have to employers.

Something isn’t working. Are universities and employers helping students to make informed choices about what to study, how to invest their time, and how to develop the skills employers want?

Are Universities to Blame?

Universities bear the brunt of the criticism for the skills gap, perhaps because students themselves don’t believe universities are adequately preparing them for the work world. One study found students actually feel less prepared as seniors, relative to their freshman year, though this may be an example of “the older I get, the less I know” phenomenon.

Where in the university would one look to improve career readiness? Perhaps the challenge lies with core curricula that fail to build foundational skills such as critical thinking and communication. It might be that disciplinary courses/majors are not aligned with industry needs, either in the sense of providing the right mix of majors, or building the right combination of knowledge, skills, and abilities within a major. Some critics have noted that universities do not emphasize building important employability skills throughout the curriculum and co-curricular activities. Others suggest there is a lack of support and preparation for the career search process.

Criticisms aside, universities certainly make gestures, and sometimes enormous investments, toward addressing these concerns. They organize curricula around ‘learning outcomes’ that focus on foundational skills such as critical thinking and communications. Colleges and departments have advisory boards to stay in touch with employers.

Universities also offer a myriad of opportunities in the classroom and in co-curricular activities to develop work world skills – undergraduate research, study abroad, experiential learning, roles in clubs and organizations, among others They invest significant resources in career centers, interview workshops, employer days, cooperative study programs, and internship program support.

Still, something isn’t working. Are these efforts sufficient and are they properly aligned with employer needs? Why aren’t students taking advantage of all the opportunities and career support campuses offer?

Are Employers to Blame?

Some critics place the blame for the skills gap on employers, arguing that employers hold down wages and push needed training back on universities – so the taxpayer can cover the cost of training instead of the firm. They assert employers want to hire individuals with every needed skill already in hand instead of providing educational opportunities to remedy specific shortcomings. Still others argue that there is simply not enough engagement by employers with higher education – that employers want to complain, but not invest in fixing the problem.

For example, employers constantly state they want students with more work experience, but according to the Society for Human Resource Managers, 40 percent of employers provide no form of paid work-based training. Many undergraduates must find paid work in the summer and/or during the school year to afford college expenses. They don’t have the financial means to pursue an unpaid internship or other unpaid work experience. The same paper suggests employers do a poor job of onboarding students, which impacts the success of the recent graduate.

In employers’ defense, universities can be complex mazes – where is the entry point to make their needs known, or to learn about curricular offerings? Small and mid-size firms in particular are resource constrained, which prevents deeper interactions with the university, makes more extensive in-house training difficult to arrange, and offers of higher pay or paid internships problematic.

Again, something isn’t working. Are employers and universities doing enough to facilitate connections? Who in the firm can best communicate what it takes to build a successful career to the university – or directly to students?

So, Who is At Fault?

Placing the ‘blame’ on any specific actor – students, universities, employers – is misguided in our view because the problem is too complex for any part of the system to solve alone. The good news is that everyone prefers a better prepared student, a more impactful university experience, a more satisfied employer. The question is how to get there.

Drawing on our experience in administrative roles, we see four overarching issues that combine to create the current skills gap: information; incentives; structures; and generational differences. We will address each issue in a separate post over the coming four weeks, including our thoughts on how to make improvements.

Where We’re Going

Information – Students don’t know enough about the likely outcomes of their choices, employers don’t know enough about the university curricula, and universities don’t know enough about what industry needs or how their graduates are faring. How do we address these information issues?

Incentives – Incentive disconnects are evident across the discussion above – what is good for the student (a flexible skill set that prepares them for a variety of jobs) vs. what is good for the employer (deep training in a specific skill set). Faculty have (some) incentives to teach their courses well but are rarely incentivized to focus on the overall curricula or student outcomes. What incentives do students have to pursue ‘the above and beyond’ experiences that may help them develop their professional skills? How do we find better alignment of incentives?

Structures – Who actually has responsibility for ensuring students are employable? The ‘core curriculum’ at most universities is a misnomer, with little coordination between component parts flung all over campus, and little accountability for students’ mastery of essential critical thinking and communication skills. Disciplinary departments are more likely to focus on capabilities necessary for graduate school than on skills needed to get a first job. How do we address these structural issues?

Generational Differences – How is this generation different and what does that mean for how universities and employers engage with them? Preparing students for success means acknowledging that some of the personal attributes in demand by employers can be cultivated through a college education - the question is how?

Over the next four posts, we will dig deeply into each of these issues and offer thoughts for addressing the challenges each presents. We believe better and more timely information and the right incentive and organizational structures, which meet the current generation of students where they are, can begin to close the skills gap. Next week: information.

Research assistance provided by Marley Heritier

“Finding Equilibrium” is coauthored by Jay Akridge, Professor of Agricultural Economics, Trustee Chair in Teaching and Learning Excellence, and Provost Emeritus at Purdue University and David Hummels, Distinguished Professor of Economics and Dean Emeritus at the Daniels School of Business at Purdue.