In our previous post we described the evidence on the “college wage premium” which shows profound differences between the median-earning high school grad and the median earning college grad, a gap that grows significantly with further (graduate) education and with experience. But these wage premium data focus on graduates who actually have jobs, and as such, significantly understate the economic returns to a college education.

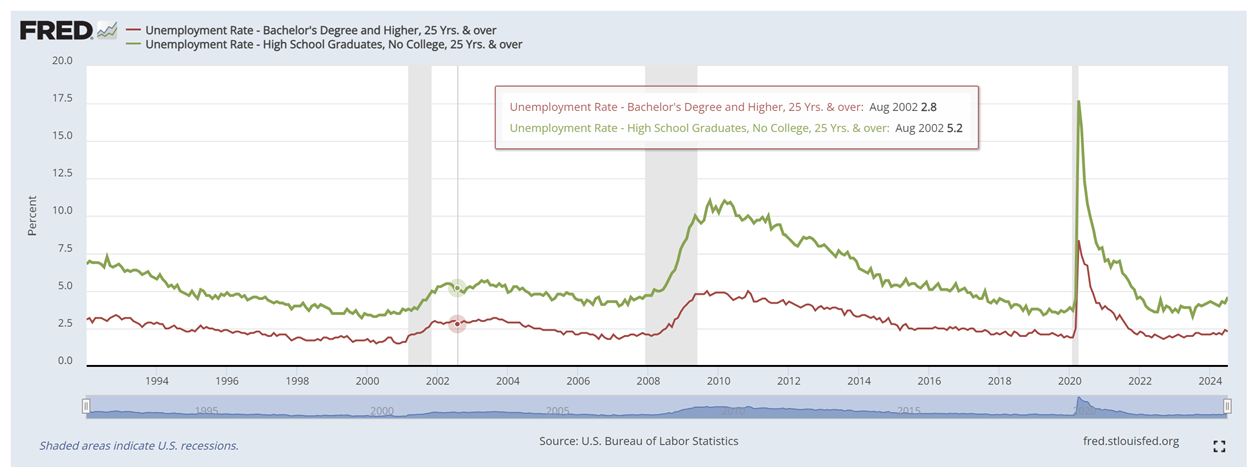

Data from the St. Louis Fed “FRED” website show that, as of July 2024, college graduates aged 25+ had an unemployment rate half (2.3%) that of high school graduates (4.6%). While neither seems high, these numbers are taken from a period in which the labor market was very tight: lots of job openings and relatively few available workers.

High school grads face a tougher job market in recessions

When the economy slows in a recession, the gap between college and high school graduates explodes. During the pandemic, unemployment among college grads was very high, at 8.4%, but high school grads had an astonishing 17.7% unemployment rate (it was more than 20% for those who didn’t finish high school)! Something similar happened during the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

Why does the unemployment rate rise so sharply for high school grads during recessions? First, many of these workers are employed in fields like construction that experience cyclical demand. Put simply, people stop building new houses and remodeling older houses when the uncertainty of an economic slowdown weighs on spending decisions. From peak to trough in the 2008-9 recession, 30% of construction workers lost their jobs! The same basic pattern is true of manufacturing workers producing durable goods: cyclical downturns hit these products and these workers harder than other sectors.

Second, when deciding whether to retain or layoff a worker during a downturn, a business needs to consider the difficulty of rehiring and retraining that worker or a close substitute for them when sales improve. For workers engaged in “routine” (easier to learn and execute jobs) it will generally be less difficult to find replacements when the economy bounces back, and therefore more sensible to lay them off in a downturn. For workers engaging in more complex tasks, the difficulty of rehiring and retraining provides insurance against layoffs during downturns. While routine-ness and complexity are not synonymous with low- and high-education levels, respectively, they are often highly correlated.

Source: “Jobs Involving Routine Tasks Aren’t Growing” Maximiliano Dvorkin, 2016, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2016/january/jobs-involving-routine-tasks-arent-growing

The astonishing drop in labor force participation

The unemployment rate represents the share of people who are actively looking but unable to find work. An even better measure to illustrate differences between high school and college grads is “labor force participation”, which reports the fraction of all people in a particular category who have a job or are actively searching for a job. In 2024, 73% of college graduates aged 25+ are in the labor force while only 57% of high school graduates aged 25+ are in the labor force - a 16 percentage point difference!

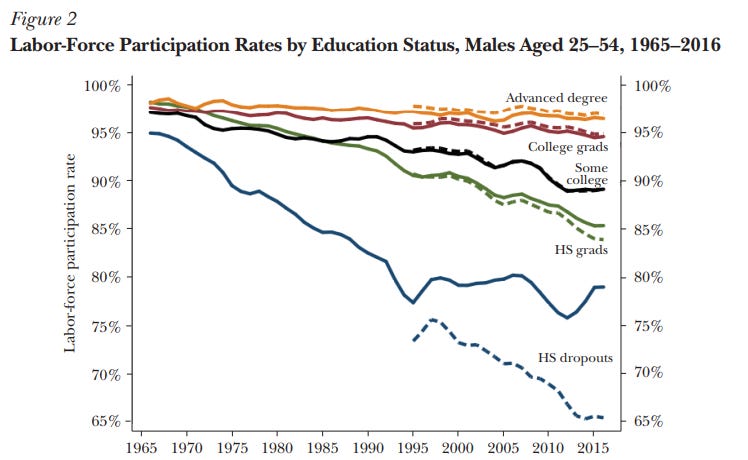

These numbers can be greatly affected by changes in the age and gender composition of the workforce. (Currently, there is a gap between men’s and women’s labor force participation, but 60 years ago it was a chasm, with more than 2 men for each woman in the labor force.) So, let’s zoom in on men in their prime working years (25-54) with data taken from a fascinating paper by Ariel Binder and John Bound, “The Declining Labor Market Prospects of Less-Educated Men”.

Figure 2 of their paper shows a pronounced drop over the last 50 years in labor force participation for men without a college degree, with this drop growing larger the less education one has.

What’s driving these enormous differences, both over time, and across educational groups?

Education and disability

Some of the variation in labor force participation is likely linked to disability. Focusing on the working age (25-64 year old) population, data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics shows that 11 percent of high school degree holders (and 16 percent of those who didn’t finish high school) had disabilities compared to 4 percent of college grads and 3 percent of graduate degree holders. This gap grows significantly as workers age. For a given age level, people with disabilities are dramatically less likely to be in the workforce than those without.

Why are these rates so different? Workers without college degrees are much more likely to hold physically demanding jobs. These workers suffer disabling injuries at a higher rate, and physical disabilities are much greater impediments to manual work than knowledge work. Further, access to health insurance is highly correlated with educational attainment (in 2021, the uninsured rate was almost four times higher for high school grads compared to college grads) and with lower incomes, less educated workers are less able to afford medical care out of their own pockets.

Family structure for men without college degrees

While noting the role of disability, Binder and Bound highlight the role of family structure – marital status and the likelihood of living at home with parents – in undermining less-educated men’s labor force participation. They argue that without a family to support, and with parents providing housing and food, men’s incentives to go find a job are greatly weakened.

The statistics are astounding. Marital rates for men without college degrees have fallen dramatically at all age ranges. For example, 83% of white male high school grads aged 25-34 were married in 1970 while only 38% of this group were married in 2015. Meanwhile, the probability of an adult man living at home with a parent has nearly tripled. These numbers look worse for younger men, for black men, and for those who didn’t finish high school. (College educated men are much more likely to be married at a given age.) Binder and Bound go on to show that labor force participation is strongly linked to these family structures.

Less education, shorter lives

Low education levels are not just associated with disability; as Anne Case and Angus Deaton have shown, college graduates live longer. In 1990, the average 25-year-old college grad could expect another 54 years of life ahead of them (that is, live to 79 years) compared to just under 52 years (or 77 total) for a 25-year-old high school grad. Life expectancy rose steadily for both groups (but faster for the college educated) until 2010 when it slowed and then started to reverse for high school grads. High school graduates can now expect to live nine fewer years than a college grad.

Why this has occurred is a subject of open research, but it seems connected to a whole host of adverse outcomes for workers who don’t complete college – worse job prospects, worse family prospects, higher incarceration rates, higher sickness and disability rates, all connected to and exacerbated by the opioid crisis and the pandemic.

Whatever the reason, pause for just a moment to re-read this sentence. High school grads can now expect to live nine fewer years than a college graduate. And while they are living, to have almost four times the rate of disability, be four times less likely to have health insurance, be far more likely to live at home with their parents, and far less likely to be married. Even at a time when the labor market is tight and unemployment rates are low, high school graduates have dramatically lower labor force participation rates than college grads. And the ones who actually are in the labor force are, on average, earning much less than college graduates.

Now, can you tell us again why people think that college isn’t worth it?

Next up: if things are so great for college grads, what’s going on with the crisis in student loan debt?

“Finding Equilibrium” is coauthored by Jay Akridge, Professor of Agricultural Economics, Trustee Chair in Teaching and Learning, and Provost Emeritus at Purdue University and David Hummels, Distinguished Professor of Economics and Dean Emeritus at the Daniels School of Business at Purdue.