Indirect Cost Cuts Could Gut University Research

How Will Universities Respond? What Are the Implications?

We interrupt our regularly scheduled Finding Equilibrium post to bring you a deeper look into an issue rolling research university campuses: the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has reduced its indirect cost rate to 15%. That sounds like something only two economists could get excited about! But this move has immediate and severe implications for university budgets and potential long-term implications for university research and its support of innovation and economic growth in our economy. Law suits are flying and a federal judge has blocked the change for the moment, but the reduction has research universities in a near panic.

What’s the Issue?

We’ll get into ‘indirect costs’ below, but at issue is how much of these indirect costs NIH wants to pay. According to NIH, in 2023 the agency invested $35B in research through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers at 2,500 universities/research institutions.

Of the $35B, $26B was for the ‘direct cost’ of the research and $9B (26%) was for ‘indirect costs’. Evidently now, NIH thinks the $9B is too much – either they want someone else to pay the indirect cost or they think universities could operate their research enterprises more efficiently.

We aren’t talking about chump change here – the reduction to 15% from the current average 27-28% would cut about $4B in indirect costs, most from university budgets. Universities in our home state of Indiana would lose about $69 million, Texas - $310 million, New York - $632 million, California - $804 million.

Source: Murphy

Before digging further, let’s set the context with some background on university finances and research funding.

How are Universities Funded?

Research universities are complex organizations with complex funding streams. Students pay tuition for educational services. Universities receive funds from operating auxiliary units: residence halls/food service, hospitals, sports programs, etc.

For public universities, states provide recurring revenue – primarily to subsidize the cost of education for their residents. (A typical out-of-state student pays 2.5 – 3 times the tuition of an in-state student.) For research (flagship) universities, some state funding supports their research enterprise. States also invest in repairs/rehabilitation to help a campus keep facilities in working order and they invest in new construction.

Donors invest in universities and a very small number of university endowments are very large. These outsized endowments are atypical – a NACUBO study on 658 universities showed 29 (4%) with endowments over $5B with more than half (335 universities) reporting endowments less than $250 million.

More importantly, returns on endowment investments are not available for the university to use at its discretion/plug budget gaps that other shortfalls create. Most large gifts are tied through a legally binding agreement to a specific investment as directed by the donor: student scholarships, facilities that support some interest/passion, etc. The very largest endowments (assets greater than $1B) are able to spend more of their endowment returns on operating expenses (about 18%) while virtually all public endowment funds (98%) are restricted in some way (APLU).

Beyond tuition, auxiliary revenue, and state and donor support, research funding makes up the other big bucket of funds.

Source: NCES (federal funding related to COVID-19 included in this figure)

How is University Research Funded?

For some research disciplines (economics for example) research costs are relatively modest and primarily involve faculty and grad student salaries. Universities can self-fund much of this research without external sponsors, so we’ll ignore these disciplines for the rest of this post.

Other disciplines such as the life and physical sciences, engineering, and agriculture require much larger outlays to fund experiments, clinical trials, and investments in facilities and equipment, in addition to salaries. These expenses are so large the university seeks partners to sponsor the research through grants

Research grants come from industry, private foundation, and government sources. But the most important sources are the federal research agencies: National Institutes for Health, National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, Department of Defense, National Institute for Food and Agriculture, NASA, etc.

Securing funds through grants is highly competitive: most federal grants have success rates of 5-10% - which means for every 100 grant applications the agencies receive, they fund 5-10 of them. (Talk about meritocracy!)

The path to landing a federal grant is a long one for a faculty member. After a Ph.D. student has spent 4-6 years in their academic program and another 1-3 years in a post doc, (some) get hired by a research university. Upon hiring, the university invests in ‘start-up package’ of funds (people and equipment) to help their new faculty member get their lab up and running and their research started. Such start-up packages can easily run $1 million or more in the life/physical science and engineering disciplines.

These start-up packages represent a major financial commitment by the university, and a high-stakes bet on whether new faculty will be competitive for federal grant funding. Those hoped-for grant funds are essential not only to support future work, but also to pay the salaries of grad students who will ultimately become the next generation of researchers!

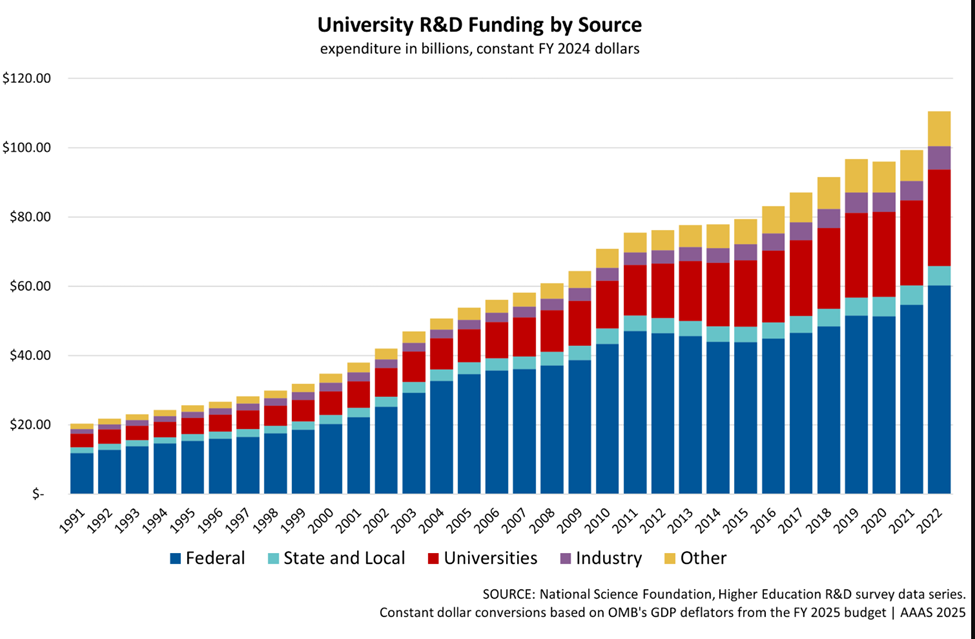

Source: AAAS

Many federal grants require the institution match the funds provided by the government at some level – 50% is common. So, if the federal government invests $100,000 in a project, the university has to come up with another $50,000. This match may be the cost of faculty time or funding for graduate students to work on the grant. The bottom-line: universities have skin in the game for any grants that require a match and for all the money they invest in start-up for new faculty.

What are Direct and Indirect Costs?

Grants cover direct and indirect costs. The direct costs of research include faculty and staff time, post docs, graduate students, clinical costs, computing, travel, supplies, small equipment, etc. But there are a lot of other costs incurred by the university that make it possible to actually do the research. These are called indirect cost or facilities and administrative expense (F&A) or overhead.

Think about a company manufacturing cars. The assembly line labor, parts, and materials are direct costs and make up a fair amount of the total cost of the car. But producing that car requires indirect costs as well: a production plant and all the equipment inside; designers, marketers, and advertising; lawyers, accountants, and finance types; HR professionals and executives.

Same for university research – it takes a tremendous investment in physical and human infrastructure before one can even compete for a federal grant. It takes labs and powerful computers and expensive equipment (you take a deep breath when you sign off on a multimillion-dollar atomic force microscope). It takes cybersecurity and IT experts, accountants to manage funds, and an army of staff to meet all the federal regulations and requirements. It takes power for the lights and heat/AC, water,… And, yes, it takes a President and managers to keep all of this stuff moving.

The bottom-line here: the term ‘indirect cost’ is a misnomer – these costs are just as real, just as important, and as such, just as direct, to conducting research as so-called ‘direct’ costs.

Source: AAAS

How Does the Indirect Cost Rate Work?

Universities recoup some of these indirect costs when the agency adds additional funds to the direct cost of the grant. (Check out this video for an excellent tutorial.) This partnership with the federal government was established long ago: universities build the physical plant and infrastructure to conduct research with the assurance that the federal government will reimburse them for part of these costs if the university successfully competes for funds. The amount of these added funds/reimbursement is determined by the indirect cost rate.

If the indirect cost rate is 45%, it means that for a $1 million grant, the funding agency would send the campus $1 million for the direct cost of the research and $450,000 to cover the indirect cost. (It’s actually more complicated than that, but we aren’t getting into Modified Total Direct Costs here!) NIH specifically takes to task some institutions with very high indirect cost rates including Harvard (69%), Yale (67.5%), and Johns Hopkins (63.7%).

Each university negotiates their indirect cost rate on a multi-year cycle with the federal government, so there is a wide range of rates. Rates vary with the kind of research being performed (human/animal trials are more costly than computational research), where it is performed (cost of living differences matter), etc.

Strict cost accounting rules are required to determine what the true indirect costs are. You need such rules to figure out how much of the cost of operating a 150,000 sq. ft. building full of offices, classrooms, and labs is actually used for research. Universities then use this information in a negotiation with the federal government to determine how much of the indirect costs the federal government will pay.

The negotiated indirect cost rate is typically less than the university’s full indirect cost. So, on top of their direct investments in research discussed earlier, universities must make up the difference between the negotiated indirect cost rate and their actual indirect cost.

What’s the Issue Again?

NIH says universities take grants at indirect cost rates lower than the federal government rate – so why should the federal rate be so high? Of course universities do this!

Think about our car manufacturer – yep, many vehicles are sold at list price, but for a myriad of reasons they will also sell below the list price – fleet sales, government sales, inventory clearance sales. The car manufacturer would go broke (or at least see their stock price plunge) if they sold every vehicle at their fleet price, but as part of an overall revenue strategy, it works.

NIH specifically calls out private foundations that pay lower indirect cost rates – say 10-12%. What’s going on? First, private foundation funding accounts for a relatively small proportion of total university research. Second, private foundation grants may only allow 10% indirect costs, but in many cases allow some costs to be included as direct costs the federal government would not – so the indirect cost rates aren’t as different as they might appear. Finally, the federal overhead rate is high in part because universities must meet a set of exacting federal standards to be eligible for grants – found in the Uniform Guidance. Contrast this massive set of requirements with the 5-page agreements that are common with private foundation funding.

The fact that federal agencies at least come close to fully funding indirect costs makes it possible for universities to accept grants at lower indirect cost rates from other funding sources - which in a real sense leverages the federal investment in research.

Who Then Foots the Bill?

At some level, this reduction to 15% sound like a good idea – who wants to invest in overhead? Faculty detest indirect cost charges – they want every single grant dollar available to pay the direct costs of research. Obviously, NIH doesn’t want to pay indirect costs.

But can you get rid of indirect costs? No. If a university is going to continue to do research of the kind that leads to scientific, engineering, and health breakthroughs, someone must pay for the labs, the equipment, the utilities, the insurance, the oversight, and the administrative support for all of it.

How Might Universities Adjust? Actions and Implications

By now it should be clear this is a really big deal (assuming it sticks). If funding for research infrastructure is reduced – or if there is uncertainty about future funding for that investment – universities will adjust by making decisions on how to best use the funds they do have. Let’s look at possible short and long run actions and implications.

Short-Run

Most (but not all) universities will find some way to keep NIH research going. Facilities and equipment don’t have to be replaced overnight, and once made this spending is “sunk” and largely irreversible (you can’t un-build or sell-off a laboratory). You’d rather take grants with lowered indirect costs rates than take none at all.

Any available indirect cost dollars will be used for essential research support staff. What is essential – depends on the university/research. Research technicians or others involved in doing research would likely keep their jobs, but staff who support faculty as they obtain and administer grants might be let go.

Staff cuts don’t mean necessary administrative work stops - it means administrative work will be pushed back on faculty. This has two important implications: faculty aren’t efficient at doing these administrative tasks and time will be taken away from what they should be doing, research. So, in an effort to improve “government efficiency”, these cuts will hand work that could be done by someone making $80,000 a year to faculty getting paid twice that (or more), and who are worse at doing it! And as an added bonus, research productivity will decline.

The university will reallocate its research funds and divert start-up funds, graduate student support, etc. to cover essential research support. A quick way to save a lot of money would be to cut the number of graduate students the university brings on and/or immediately freeze all new hiring in fields requiring large start-up packages (in part because you don’t know if the new hires will be able to secure grant funds anyway). If you typically hire 50 people a year who need $1 million start-up packages and don’t hire any, you’ve saved $50 million (over time). Of course, you’ll have to do that again the next year and the next because the cut in indirect costs has created a recurring budget deficit…and research output will steadily decline.

Longer-Term:

Universities will look for ways to get more efficient in conducting and managing research. There are likely modest opportunities here – but we seriously doubt anyone is going to find enough efficiencies to bring their indirect cost rate down to 15% (at least for science and engineering research).

Universities could reallocate funds from other functions: reduce student services, increase student-to-faculty ratios, dump student success programs, etc. No free lunch here – simply starving one part of the university to make up for short falls in another.

Universities will try to shift research to funding sources that will cover indirect costs. Those sources look few and far between – private foundations already pay a lower indirect cost rate. Perhaps sponsored research from industry could grow, though for many reasons industry has largely retreated from basic science.

Universities will look for other fund sources to cover indirect costs. This isn’t easy either: as discussed earlier, the folks who write checks to universities have strong opinions about where their money goes. Many university fund sources are tied down by legally binding agreements, but others that could be legally shifted would border on the unethical. You could, for example, sharply raise tuition and use all the new revenue to pay for research overhead instead of improving students’ educational outcomes. (We don’t really want to think about how that will play with a state legislature…)

While there has been some speculation that this cut was aimed at elite private universities, the reality is that the size of their unrestricted endowments, and their tuition pricing power, means they may be able to emerge from all this relatively unscathed. Options are fewer in places where budgets are already stretched – mainly public universities and privates outside the elites.

These other universities will gradually retrench and narrow their research footprint – perhaps focusing on research areas where indirect costs are lower, moving from clinical to computational research for example. Hiring freezes to avoid start-up packages will steadily winnow down science and engineering faculty. Physical infrastructure will depreciate and capacity will be lost. When that multi-million-dollar atomic force microscope needs replaced, where will the money come from?

If research capabilities are reduced at universities, the best scientists will look for other places to work – perhaps industry or in the country they were born.

Possible Funding Agency Actions?

If transparency around indirect costs is an issue, federal agencies could deal with that in their indirect cost negotiation – bring the hammer down on ‘offenders’ instead of on everyone. Or they could change the way they reimburse indirect costs – ask universities to itemize those items as direct costs in grants the way some private foundations do.

Federal agencies could also do something useful and drop some of the regulatory/reporting burdens they impose to cut the cost of compliance for universities. Some of these rules and regulations are essential for basic accountability, but perhaps the federal government could learn something from private foundations here.

Source: COGR

Final Comments

Please understand: we are economists so we like efficiency! If there are solutions out there that help our US biomedical research enterprise operate more efficiently and effectively, by all means we need to pursue them. However, we believe such work is best done with a scalpel and not a chain saw…

Our research ecosystem has evolved to the point that most basic/fundamental research happens at research universities and most development/commercialization research happens in the private sector. Ultimately, if funds aren’t found to cover indirect costs, we unwind (or at least severely degrade) an ecosystem that supports innovation and drives growth in our GDP.

Next Week

Back to our regularly scheduled programming: we’ll take a look at the impact rankings have on universities and university decision-making (unless another bomb is dropped on higher education that we feel compelled to write about).

Research support provided by Marley Heritier

“Finding Equilibrium” is coauthored by Jay Akridge, Professor of Agricultural Economics, Trustee Chair in Teaching and Learning Excellence, and Provost Emeritus at Purdue University and David Hummels, Distinguished Professor of Economics and Dean Emeritus at the Daniels School of Business at Purdue.

Great insights, as always! Could you please elaborate a bit more on this statement: "Perhaps sponsored research from industry could grow, though for many reasons industry has largely retreated from basic science."

This is the clearest, most detailed account I've seen of indirect costs. I'd love it if in a future post you'd do a deep dive on the other half of the post's title -- that is, on the research itself. In other words, although federal grants are meant to support research, it can seem to some faculty that the tail is wagging the dog -- that only research with the potential to support big grants is encouraged. (And "encouraged" can be translated into clear economic incentives, like higher salaries or even keeping your job at all). Such an incentive system could distort science such that the likelihood of high funding, rather than scientific criteria, shapes the research agenda. And of course whole fields, like the humanities, become increasingly irrelevant in this kind of climate. All told, universities' dependence on federal grants seems to have deeply re-ordered their research (and arguably educational) priorities. I wonder if it would make more economic sense to leave the most expensive research to industry? Or maybe what I mean is for universities to adjust to that reality, as that seems to be what's already happening for some AI research and in terms of personnel -- something like 50% of scientists are leaving academic science, and many seem to be leaving for industry. At any rate, if you find yourselves without a topic to write about, I'd love to see a 'companion piece' to this terrific post!