In our series of posts on faculty tenure, we saved the most misunderstood, controversial, and most important issue for last – academic freedom. Academic freedom is a core tenet of faculty tenure, but it has also been a fundamental operating principle of U.S. higher education – supporting institutional autonomy and self-governance.

The idea of academic freedom as a right of tenured faculty and as a principle of institutional autonomy is being challenged as never before. This post explores academic freedom as one of the primary objectives of tenure: what it is, why it is important, why it is under fire, and how it impacts the choices that faculty make in their research and teaching.

Note these questions are distinct from an issue currently roiling universities: how the reliance on external funding challenges institutional autonomy and academic freedom. We’ll take that on in a future post.

What is Academic Freedom?

The American Association of University Professors provides a formal definition, but the essence of the idea is faculty can’t be fired for what they teach or the research they do – as long as what they are doing is in their academic field. They also can’t be fired for speaking their mind on matters of institutional governance or for expressing themselves outside the university on matters that are important to them.

The idea seems simple enough: faculty are to be left alone to do their work. In practice, this seemingly innocuous idea is anything but simple and it generates a lot of heat – in part because of a lack of understanding of what academic freedom is and what it is not.

Academic freedom does not mean a faculty member can say anything they want in a classroom (they can’t). It does not mean they can behave in any way they want (no again – university policy and regulations (and our legal system) govern faculty behavior). It does not mean they can publish anything they want (the peer review process means other experts dictate what gets published).

While there are limits and constraints, academic freedom does mean that tenured faculty have a lot of control over what they teach and the focus of their research.

Why Does Academic Freedom Exist?

The short version is new ideas aren’t often well received – put forward a new way of doing something or a new way of thinking about something and someone’s proverbial ox is gored. That can be very problematic for the person with the new idea!

There is a long history of scholars being persecuted for new ideas (think Galileo and his crazy notion the Earth rotated around the Sun, Darwin and the theory of natural selection, etc.)

A more recent example comes from the “difficult years” of McCarthyism in the late 1940s/1950s when fears that Communists had infiltrated universities (along with other institutions) were pervasive. In a 1955 survey of 2500 social science faculty, 990 incidents were reported in which an accusation was made against at least one professor. About one-half of these led to some form of sanction and “104 faculty members were forced to resign for political or religious reasons” (Lazarsfeld & Thielens, Jr., summarized in FIRE).

Formalized in the 1940 AAUP Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, one pillar of tenure as a formal condition of employment was academic freedom: allowing scholars to do their work with the confidence that no matter who didn’t like their ideas, they got to keep their jobs. At least those faculty with tenure do…

Does Academic Freedom Still Matter?

Galileo got in trouble with the Church about 500 years ago and Senator McCarthy began his search for Communists 75 years ago. Do the protections of academic freedom for faculty still matter in the 21st century? The answer is a resounding yes! In our leadership roles, we have dealt with plenty of issues where the academic freedom of a faculty member was challenged.

Research findings put a company’s product in a bad light – you need to rein that rogue faculty member in! A study offers up a controversial position on a social issue – watch the internet trolls bombard the faculty member with disgusting comments and threats. A student hears a perspective that is not aligned with their view of the world – get that faculty member out of the classroom!

Such pressures come from inside the academy as well – if you are in a pre-tenure or non-tenured position, and another (tenured) faculty member really doesn’t like what you are teaching or the focus of your research, you may find yourself looking for a job with your tenure denied or your annual employment contract cancelled. Tenured faculty have no such worries.

This stuff happens – regularly – and protecting the faculty member’s right to keep their job while they do their work in the face of such pressures is what academic freedom is all about. Basically, it guarantees the university has the faculty member’s back.

Why Should Society Care about Academic Freedom?

Good research changes our understanding of the world…great research changes the world. If we already knew everything there would be no point in doing research. When you change an understanding…of politics, history, economics, biology, engineering, soil science… someone is going to be unhappy with the new understanding. So, all good/relevant research offends someone, hence the need to protect the researcher.

Think about research in areas that have been called out for funding cuts such as racial inequality and health access, vaccine hesitancy, and climate science. Do we really think we are better off if we don’t know why certain groups have worse health outcomes, why people don’t want vaccines, or how sea level rise will affect coastal communities?

Great teaching works the same way – challenging ways of thinking, deepening perspectives, building skills in discernment. Academic freedom empowers faculty – who have spent years mastering their discipline – to make decisions on what material needs to be taught and how to teach it.

Constraining these rights of faculty to choose what they research ultimately limits creativity, shuts down promising ideas, slows/stops innovation and progress. Restricting what faculty teach leads to groupthink and limits development of critical thinking skills by students.

Why is Academic Freedom Under Fire?

Control, accountability, and politics. The fact that academic freedom gives faculty the right to do their jobs without outside influence is infuriating to some outside influencers. Public universities are funded by taxpayers, and governed by Boards that are typically appointed through a political process. And, you are telling these elected officials and governing boards to keep their hands off what faculty teach and research, the broader curricula, who is hired and retained? That just doesn’t sit well…

In fairness, many of the political critiques of the university cast political intervention as a necessary antidote to the university’s own failure to protect academic freedom as well as the decline in public trust of universities.

They would claim that politically unbalanced hiring or cancelling `controversial’ speakers is evidence that academic freedom as currently practiced is a one-sided affair. Those paying the bills question the cost of education, student debt, student preparation for the work world, etc. And because the university and its faculty can’t be trusted to right their own ship, politicians will do it for them.

While there is some truth to the idea that universities have provided plenty of kindling for the fire currently burning, even well-intentioned interventions can spin out of control. What starts with a call for balance can quickly land on the outright prohibition of teaching particular ideas and/or directing research agendas in destructive ways. We’ll dig deeper into this in a future post.

Academic Freedom and Research in Practice

Academic freedom as guaranteed through tenure means faculty have the right to ‘publish findings without interference’. But this is far from a blank check to work on whatever you want. Four practical constraints shape the research that a faculty member does and the impact that it has.

First, who gets to do research? You don’t have much academic freedom if you don’t have a job, and you don’t have time to do research if you aren’t hired into a tenure-track position. While faculty are involved in the hiring (and promotion) process, central administration typically controls whether or not available faculty positions enjoy the protections of tenure.

Second, who decides what faculty work on? University research (particularly capital-intensive research in engineering, science, medicine, agriculture,…) is dependent on competitive grants to support the work. Even for non-capital-intensive disciplines such as some of the humanities and social sciences, you still have to find funds for graduate students, post docs, data collection, travel, etc. And the federal agencies, NGOs, and private sector firms that sponsor these competitive grants/provide such funding determine what topics/areas get funded.

Yes, faculty can be engaged by funding agencies in helping define topics/areas. And, faculty have the freedom to compete for the funds and to do the work (if they are one of the few to get funded), but this is all within the constraints of the grants program that dictates what kind of research proposals the funding agency will consider. In many disciplines (but certainly not all) this affects who gets tenure: no matter how talented you are, if you can’t fund your research program, no tenure for you.

Third, faculty peers can limit the research domain. Before your research gets published, it must pass muster with a group of peers working in your discipline/general area. While some would say this process leads to insular thinking/constraints on bold ideas in a discipline, there is a strong argument for such a hurdle.

The standard that a faculty member must meet - presenting compelling evidence that their idea/perspective adds something to what is already known in a discipline - separates a faculty member from a You Tuber. Pitching a new idea: not so hard. Pitching a new idea with the evidence that it clearly adds to/turns over the knowledge we have accumulated in a discipline over the course of human history: hard!

Fourth, universities face a dilemma when trying to be relevant with their research agenda. For research to have an impact, people need to know about it. But bringing attention to the outcomes of research on a contentious issue makes it much more likely you will invite complaints. Would you rather remain quiet, and uncriticized, or highly public and face a backlash? Such increased scrutiny can have the unintended consequence of faculty just keeping research quiet, at best, and shifting the direction of their work to something less relevant at worst.

The bottom-line: faculty have some leeway in the research they do and how they communicate their work. But, the constraints imposed by funding agencies and peers are real, as are the implicit pressures that come with working on relevant, contentious issues.

Academic Freedom and Teaching in Practice

What does it mean to ‘teach without interference’? In preparing a course, a faculty member makes thousands of decisions, large and small, about what content to include in their course. (The exception is new faculty, who try to include everything known to humanity in their course the first time out – trust us, we have been there...)

Academic freedom says this choice of what to include in the course and how to teach the course belongs to the faculty member – they are the disciplinary expert, they choose the content and the approach.

Note this does not say faculty have the right to spout off about something unrelated to their discipline in the course – they don’t. If you are teaching calculus, academic freedom does not mean you can take the first 25 minutes of class railing about the Russia-Ukraine war, local zoning issues, or your busted NCAA basketball bracket (unless you can somehow weave a team’s win/loss trajectory into a discussion of derivatives).

This business of what is germane and what is not may be pretty straightforward with a calculus class, but can get far trickier in the humanities and social sciences – and likely focuses as much on how a topic is discussed as the topic itself. Faculty have the right to bring any contentious topic into their course if relevant to the course. That said, faculty also have a responsibility to students to help them put that contentious topic into context so they can form their own opinions about said topic – and to have a reasoned, civil discussion about it.

To take a current example: the Trump administration is in the middle of igniting the biggest international trade war in the last century. And in the view of these authors (one of whom is an actual expert on the subject), these policies are likely to lead to a lot of grief. But to teach the topic properly one needs to acknowledge that there are theoretical economic arguments that describe the conditions under which tariffs can raise national incomes, or lower them. And other arguments about how tariffs can be used to redistribute income within a country. And other arguments about how tariffs can be used to pursue national security or other non-economic objectives. And there is a lot of evidence about all of the above.

Strictly speaking, academic freedom as conventionally conceived would allow a faculty member to cherry-pick only those arguments that support their own view of the topic, perhaps inflected by support or dislike for the Trump administration itself.

In our experience, faculty members generally do their best to reflect conflicting major strands of thinking and evidence on controversial topics. But this balancing act is constrained by the faculty member’s editorial function in constructing a class – there isn’t time to talk about everything. And providing a balanced treatment doesn’t mean that students actually *hear* the balance in what is presented. Students’ own prejudices about the subject can influence what they remember.

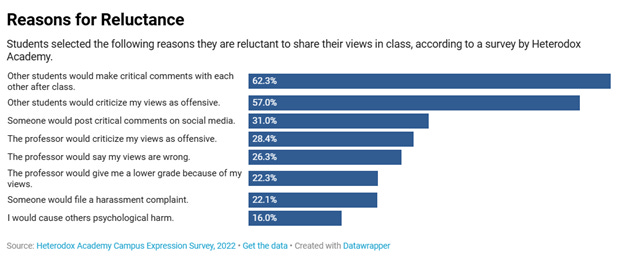

Many current challenges to academic freedom are based on some vague allegation that universities ‘indoctrinate’ students. There are some students we wish we could indoctrinate with economics – getting them to read the syllabus is challenge enough! That said, when it comes to affecting views and how they are shared, students likely have far more influence on one another than the instructor does.

Source: Chronicle.

Upshot

We have argued there is societal value in allowing faculty to do their work as free from constraints as is possible. Tenure protects this right by connecting continued employment to that freedom. However, only about 1/3 of the faculty in the US enjoy the protection of tenure. If freedom to make choices about research and teaching is so important to the operation of the academic enterprise, why do so few faculty enjoy it? Is the promise of continued employment the only way to guarantee that right? We will take this issue up next week.

More broadly, issues of trust and accountability set up the fundamental problem that universities face concerning increasingly suspicious external stakeholders. We ask them to trust us as experts: to make good decisions about what we research, what we teach, who we hire and promote, how we operate our campuses.

Our external stakeholders have very little evidence on which to base criticism of any of the above because, as non-experts, they don’t know what good research is, or how to teach a controversial topic, or who the best candidates are for hiring and promotion, or even how to operate a university. So they have to trust our judgments, and that trust takes the shape of academic freedom, as protected by tenure, and institutional autonomy and self-governance, which higher education has enjoyed over time.

What we are learning now is what happens when the non-experts stop trusting us.

Next Week

The current tenure system has clear pros and cons – tossing it is a bad idea, but so is preserving the status quo. We will share our thoughts on some alternatives in our next post.

Research assistance provided by Marley Heritier.

“Finding Equilibrium” is coauthored by Jay Akridge, Professor of Agricultural Economics, Trustee Chair in Teaching and Learning Excellence, and Provost Emeritus at Purdue University and David Hummels, Distinguished Professor of Economics and Dean Emeritus at the Daniels School of Business at Purdue.

Thanks for clarifying the topic of which I Only understood at the surface.

Great installment in a series that just keeps getting better.

I agree that the grant system and peer review provide some boundaries on research/accepted speech. But I also wonder if self governance in general is a kind of pie-in-the-sky approach. As mentioned, when it fails, it can lead to things like McCarthyism or the recent backlash over perceived institutional stances on Israel/Palestine.

Reminds me a bit of the financial-services industry's attempt to self regulate via FINRA: it appears effective in good times, but it is in the in bad times that it seems to amplify harm as well (or at least it amplifies public outrage).

It would be interesting to measure a given university's retractions vs. let's call them "faculty disciplinary events" over time. "Nature" recently approached this from a slightly different angle:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00455-y